In 2024, I read 39 books, mostly returning to literary classics and works that had previously touched my soul, rather than exploring new titles.

Here are a couple of highlights from my reading this year. You can find my recommendations for previous years here (since 2017).

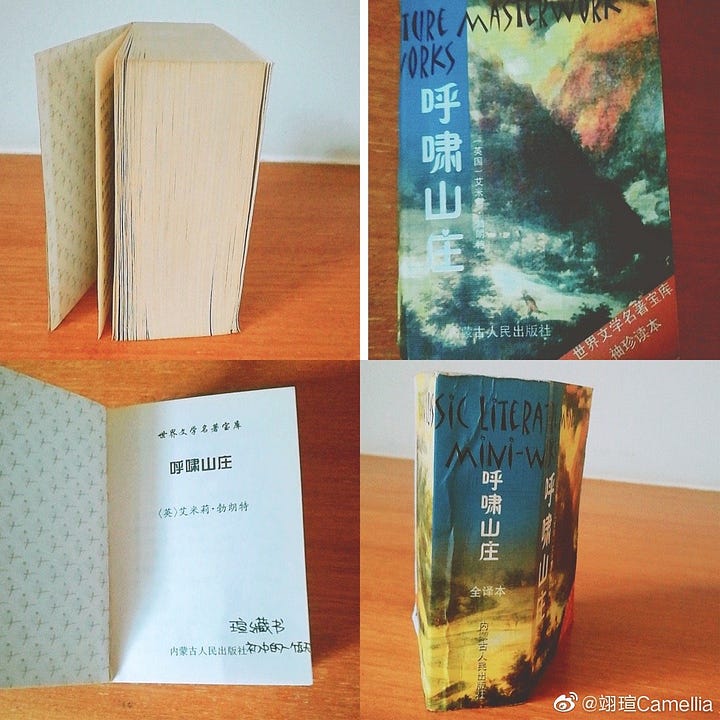

A Wild Spirit on the Moors: Revisiting Wuthering Heights

On a drizzly afternoon in Haworth, I visited the Brontë parsonage. As I walked through their home in the soft Yorkshire rain, I felt quite close to those literary spirits from nearly two hundred years ago. My mum took a lovely photo of my old copy of Wuthering Heights from my school days. Everything felt rather real there: the desk where the sisters wrote, the moors where they wandered, and the time when they had to publish under men's names.

Standing at that old desk, I thought of Catherine's powerful words: "Nelly, I am Heathcliff! He's always, always in my mind: not as a pleasure, any more than I am always a pleasure to myself, but as my own being." It's a perfect capture of love really - two souls becoming one.

Wuthering Heights swept through my teenage years like a wild wind from the moors. The love between Catherine and Heathcliff was never meant to be a pretty fairy tale, but rather a dark, passionate story. As Catherine says:

If all else perished, and he remained, I should still continue to be; and if all else remained, and he were annihilated, the universe would turn to a mighty stranger.

Walking on those same moors, I finally understood why Heathcliff cried out: "Be with me always—take any form—drive me mad! only do not leave me in this abyss, where I cannot find you!" It's a bit mad, perhaps, but terribly sincere - rather like a sort of spiritual opium, showing us love at its most extreme.

In our sensible modern world, Wuthering Heights reminds us that we humans are deeply emotional creatures - that's what makes us different from machines and other beings. When Catherine declares: "If he loved with all the powers of his puny being, he couldn't love as much in eighty years as I could in a day," you can't help but feel that raw human passion.

Standing at the parsonage window in the fine rain, I looked out over the rolling moors. This isn't just a writer's home, but a place where love and freedom still echo. In our busy world, perhaps love is our last real refuge. Why not get swept away by it, just once, and make our own unforgettable tale?

The Secret of the Golden Flower: A Dialogue Between East and West

After spending last year with Jung's Red Book, I found myself looking at The Secret of the Golden Flower rather differently. Jung wrote a foreword to this Taoist text, based on Wilhelm's German translation, and it's fascinating how Eastern and Western wisdom meet in his thoughts. I was quite taken with Jung's words: "All my works are tasks imposed on me from within, they came upon me with a sort of fate. What I wrote came from questions my inner self posed."

In his notes on The Secret of the Golden Flower, Jung spotted something rather remarkable - this ancient Chinese text about inner growth matched his own ideas about what he called "individuation". The golden flower in the book, meant to show spiritual awakening, fits rather nicely with Jung's idea of the "Self".

Reading through Jung's commentary again, I was particularly moved when he wrote about feeling terribly alone at first. He knew people wouldn't like hearing that our rational world needed some sort of balance - it wasn't exactly a popular idea at the time. This reminded me rather strongly of the old Taoist notion of walking alone with the spirit of heaven and earth.

Jung was quite taken with the book's idea of "turning the light inward". He saw it as remarkably similar to his own method of active imagination. As he put it, he had to say things nobody wanted to hear - rather like how The Secret of the Golden Flower suggests that true awakening often means questioning what everyone takes for granted. Reading his commentary, I better understood his approach: letting that inner spirit speak freely, not expecting much excitement but offering something our modern world rather needed. It's exactly what the ancient text says about being truly sincere in one's practice.

Growing spiritually isn't just about being sensible - you've got to be brave enough to face your darker side too. Jung found this often left one feeling quite alone and misunderstood, but it's precisely in these lonely moments that our deepest thoughts come. I felt as if I could see a tiny light inside - not very bright, but warm and comforting in its way. That's what Jung meant, I suppose, about the golden flower blooming when we dare to look at our darker side.

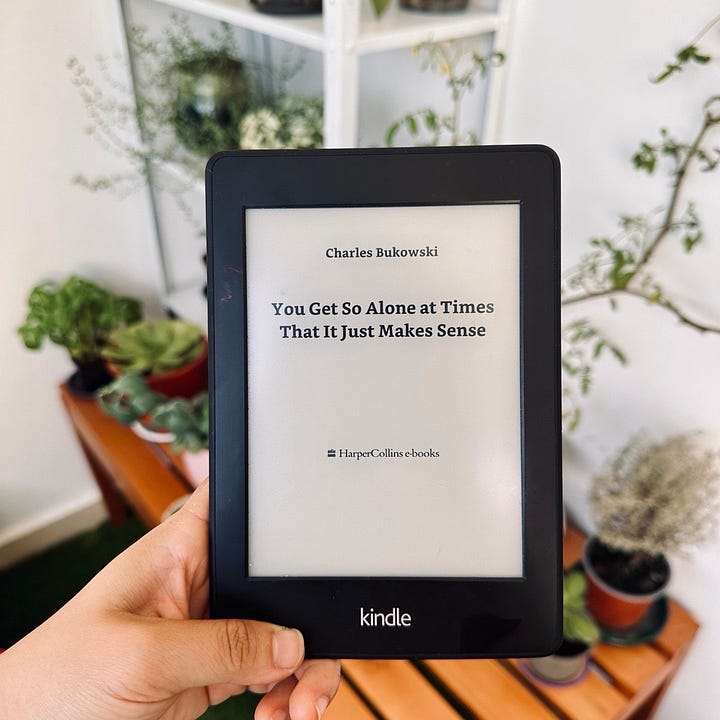

Charles Bukowski: The Poetry of Solitude and Reunion

On a London afternoon in 2019, I first encountered Bukowski's You Get So Alone at Times That It Just Makes Sense in a floating bookshop along the Thames. Having no cash on hand at the time, I regrettably had to leave the book behind. Yet fate, with its peculiar sense of drama, would reunite me with this volume years later through an algorithmic recommendation, like encountering an old friend after a long absence.

It was during a twilight hour in Aveiro, Portugal, where I attended a unique poetry reading in this city of interconnecting canals. The venue was an old beerhouse, its wooden floorboards creaking softly with age, while golden light from frothy pints flickered across the room. As I stood to recite one of his most famous verses, a hushed stillness settled over the crowd, broken only by the occasional clink of glasses.

there is a place in the heart

that will never be filled

a space

and even during the best moments

and the greatest times

we will know it

This poem seemed to speak to that unfillable void present in everyone's heart. As I alternated between English and Chinese readings, the Portuguese audience in the pub responded with knowing smiles. In another poem, Bukowski wrote: "agony sometimes changes form but it never ceases for anybody". This raw analysis of life's essence resonated deeply with everyone present.

By the canals of Aveiro, as dusk settled, I recalled another line from his collection: "it has been a beautiful fight. still is." Perhaps this best captures Bukowski's most authentic portrayal of life: even in our loneliest moments, we continue to fight, seeking beauty in our existence.

After the reading, a local poet remarked, "Bukowski helps us understand that solitude, is a form of strength." Indeed, as he wrote in his poetry, "waiting is another word for dying", yet we persist in waiting, hoping, searching for light in life's crevices.

In Bukowski's world, authenticity always trumps embellishment, and even in pain, one finds the flavour of life. This perhaps explains why his works transcend time and space, striking chords across different languages and cultures. That poetic evening in Portugal, those shared smiles among strangers, all confirmed the eternal theme in Bukowski's writing: in our solitude, we find one another.

Borges: Searching for Eternity in Life's Labyrinth

My first encounter with Jorge Luis Borges occurred during a journey to Buenos Aires. Our guide led us along Calle Colón, where the café that Borges frequently visited still stands. Seated in this centenarian establishment, peering through aged windowpanes at the street scene beyond, one could almost glimpse the author crafting his dizzying tales. The rising steam from mate tea, ancient wooden furnishings, and yellowed newspaper clippings on the walls all whispered tales of a bygone era.

It was here that I opened Borges' Ficciones. His writings resemble an intricately designed labyrinth, with each turn revealing astonishing philosophical treasures. In The Garden of Forking Paths, he presents us with one of his most profound concepts through the character Stephen Albert's explanation:

This web of time – the strands of which approach one another, bifurcate, intersect or ignore each other through the centuries – embraces every possibility. We do not exist in most of them. In some you exist and not I, while in others I do, and you do not.

His conception of time particularly captivated me. The notion in The Garden of Forking Paths that multiple realities might coexist simultaneously prompted me to reconsider the relationship between fate and choice. Whenever I face life's crossroads, I recall this image: perhaps in some parallel universe, another version of myself chose a different path.

In The Library of Babel, Borges writes: "The universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite and perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries." I began to understand why his works consistently both perplex and fascinate: in his world, the boundary between reality and fiction blurs, and through this very ambiguity, we see life's essence more clearly.

Walking through the evening air of Calle Colón, the street lamps stood like beacons in Borges' eternal labyrinth. The city seemed to become a footnote to his works: each corner potentially leading to a new story, every doorway concealing infinite possibilities. His writings serve as a magical mirror, reflecting our deepest confusion and desires, guiding us through a maze of words in search of answers about eternity.

Borges' works transcend mere literary creation; they are metaphors for life itself. Each rereading reveals fresh insights, perhaps this is the true allure of classical literature. In his writings, time ceases to be a unidirectional river, instead becoming an eternally forking garden where we encounter countless possible versions of ourselves.

Conversations with God: A Dialogue Between Love and Fear

During a conversation with

, he shared a fascinating experience. Within a single month, he had three "chance" encounters with the book Conversations with God: first, when a friend casually recommended it, which he initially dismissed; then at a gathering, where he overheard two people engrossed in discussion about it, which piqued his curiosity; and finally, when a guest speaker coincidentally pulled the very same book from her bag, prompting him to finally get a copy. As he recounted this series of coincidences, I was reminded of one of the book's core messages:There are no coincidences in the universe.

This brought to mind my own first encounter with this book. The book found its way to me through one of the online KOL’s recommendations during a period of profound confusion and anxiety as I approached my thirtieth birthday. I wondered: could these seemingly random encounters harbour deeper meaning? Perhaps life, in its mysterious way, had delivered this book to me precisely when I needed its wisdom most.

The book's discussion of love particularly resonated with me. Walsch writes that "Love is all there is" and that "Fear is that which you are not." We're accustomed to attaching conditions to love: "I'll be kind if you're kind to me" or "I'll give if you meet my expectations". But the book challenges us to understand that true love exists without conditions, without expectations of return. Like sunlight blessing the earth indiscriminately, or a mother's boundless love, requiring no proof or reciprocation.

One of the most powerful teachings in the book is that "Fear attracts like energy." Reflecting on my relationships, I recognised how often I had erected barriers out of fear of being hurt, or held on too tightly out of fear of loss. Yet when we truly comprehend the nature of love as described in the book - as the fundamental essence of all existence - we realise these fears arise from our misunderstanding of what love truly is.

This year, the book appeared precisely when I needed answers, helping me re-examine life's perplexities and uncertainties. As Walsch teaches, when we're ready to receive wisdom, the universe provides the perfect teacher.

Thank you for the interesting reading list.

Some of your title suggestions I have not read. I will try and seek them out but first I must make inroads to the pile of books sitting on my desk table -- they have been sitting there for a while; non fiction and fiction.

The trouble is I am all eager to read and as you know the ebbs and flows of the creative life kind of dampens the energy so they remain unread, but I feel I could read 4 to 6 books a month when there is an uptick or surge in interest and energy or season is right. I plan to read more this year too.

Enjoy your reading in 2025 CY.

The Classics heal and offer collective wisdom on a platter. I prefer reading the primary sources anyway. Going to derivative; secondary sources or spin-offs are essentially saying the same thing and you realize modern works are subsequently flogged to death with no new message to tell. For example there are so many book spin-offs to the craft of writing fiction. "Aristotle: On Poetics", expounded on the craft millennia ago - that is all you need with his three Act Story Structure: beginning, middle ( Acts I, II, III) and is the basic requirement what commercial publishers ( gate keepers) and Hollywood (screenwriters) want on a first few page reading before assessing the work for publication.

Also perplexities of life for me usually means things are seen from one rigid point of view only . There are other points of view that makes things clear as viewing through perspex; a multi dimensional to thinking and seeing; other worlds are possible. These days we have two lives if we desire: the physical and the digital. Some will say holding a hand of a friend or relative that needs care and comfort can not be replicated digitally ? Perhaps not and therefore the physical world has limitations. Then you have the digital that amplifies possibilities. This is were anything is possible like enduring friendships that last forever beyond the physical. Love lasts forever. So the question what does one want? physical or digital? or does one hedge their bets for both ?